In the lead-up to the Dingle Food and Wine Festival, local farmer Colm Murphy pulled up beside me in his aging black pickup and produced a few ears of corn from the back. He wanted to know if I thought the corn was good enough to sell at the festival market, so I duly took them home and cooked them (husk and halve, steam for 20 minutes, slather with Irish butter. Cost, excluding the butter: a caffe americano from our shop, given in thanks). Not only was the corn good, it was so good that time slowed down for a glorious, butter-dripping-down-my-fingers moment of sheer satisfaction. This food was local, fresh, and so bursting with flavour that all seemed right with the world.

Food is a multi-billion euro industry in Ireland, and we are really good at it. Perhaps it’s not as glamourous as other parts of the economy, and perhaps it’s so ubiquitous that we take it for granted. We eat it, and we find it stacked in our shops, cooked in our restaurants, and scattered everywhere in the countryside. It’s hard to think of Ireland without the sheep on the hills and cows on the grass, and it’s hard to remember just how unusual freely-grazing beasts are in developed countries. We also have pigs, chickens, ducks, goats, and beyond them, a sea that still contains a dazzling array of fish. We might complain about the rain, but our mild climate is well suited to most vegetables, fruits, grains, herbs, and even some nuts. We also have wild foods, including chef Kevin Thornton’s favourite ingredient, marsh samphire, which grows sea-sprayed along our coastline (cook for 30 seconds in a hot pan with a bit of olive oil. Cost: a great day out foraging with the family).

Just as important as the abundance, we have a tradition of growing, harvesting, raising, and cultivating food. We like to talk about slow foods, but 50 years ago in Ireland, almost all food would fit that category. We have a burgeoning “grow your own” movement and allotments springing up everywhere. It all seems so new and chic, but it wasn’t so long ago that many of our forebears enjoyed their own vegetables. My father had his plate filled with a seasonal harvest of potatoes, carrots, turnips, onions, spinach, and fresh herbs, all grown in the family haggard or garden plot in Cork (combine all of the above for a winter stew, adding water and vegetable stock, and simmer until cooked. Cost: a few seeds, a bit of weeding, and a beer bath or two to catch slugs. Prayer – optional – “Bless us our Lord, and these Thy gifts, which of Thy bounty, we are about to receive…”)

We can grow food, we can cook it, and we make great products with it. Patisserie Regale’s Paneforte from Urru in Bandon, is a good example (serve thin slices with coffee. Cost: €17 for 12 – 15 portions). Or visit Galway and McCambridge’s for James McGeough’s Connemara Air-Dried Lamb (serve on Irish brown bread with Buílin Blasta’s pineapple and chilli chutney. Cost of the lamb: €4.42 per pack.) Strolling through shops such as Morton’s (try their plum pudding) or Fallon & Byrne (a good source of Bluebell Falls goat’s cheese) lead to discoveries of all sorts – Irish vinegars, cookies, breads, meats, or smoked salmon (Ummera is one of my many favourites – try drizzled with a little lemon. Cost: €13.40/200gm).

It puzzles me that given the abundance and quality of food in Ireland, Irish foods seem to be held in such low esteem here. How else is it possible to explain that, in the height of apple season, our local supermarket currently stocks apples from Germany, Holland, South Africa, Chile, France, New Zealand, and only one option for Irish eating apples? It’s not about the price, since the Irish apples are by no means the most expensive of the lot. Maybe we have grown so accustomed to foods shipped in from abroad that we don’t question it anymore, but can an apple that has spent so much time on lorries and ships taste as good as one plucked fresh from an Irish farm? Unsure? Then head to your local orchard or else to Tipperary, to the Apple Farm, and savour one of Con Traas’ Elstars, which are just coming into season (no recipe needed – just sink your teeth into it. Cost: €7.50/6 kg, which works out at 18 cents each).

How else besides low esteem could we explain how Tesco has pulled so many Irish foods off their shelves and gotten away with it? Even in these straightened times, it’s inconceivable such a move could even be considered in other countries such as Italy or France. Could you imagine telling the French you would no longer stock Brie or telling the Italians that Parma ham would be replaced with a cheaper British alternative? I think not. And yet, we’ve only had one protest, from some very angry potato farmers, who thought Irish roosters deserved a place on Irish shelves (roast one Irish rooster potato, preferably not one thrown in protest – top with sour cream and fresh parsley, cost: €4.99/10kg bag, from O’Connors farm in the Maharees).

Don’t get me wrong – I am not one who believes that we should be insular, “patriotic” in our purchases, or only limit ourselves to Irish produce. I’m delighted to have access to foods from abroad, and I love cooking and eating them. It’s just that we have so many great foods here, foods that are truly world class. Ross Lewis of Chapter One has turned me onto organic cold-pressed virgin rapeseed oil from Drumeen Farm in Kilkenny. They have had a fire on the farm, but the oil is still available at Joel Moore’s stall in the Clonmel farmer’s market (drizzle over salad. Cost: €6.50/500ml). I’m also constantly amazed at the quality of our local fish and often so disappointed when I travel. If you’re lucky enough to have a good fishmonger near you, such as Beshoff’s in Howth or Ó Catháin’s in Dingle, one who can suggest the best of the fresh, local catch, you know what I mean.

Or, consider Irish dairy. Not only do we have a huge range of sublime cheeses – cheeses that consistently bring back top awards from international competitions, but we have the best milk and cream in the world. I don’t say that lightly. I have travelled widely and have never tasted better. In fact, we started our ice cream business because my brother and I, raised in the U.S., were in such awe of it (whip 227ml of fresh Irish cream with 1.5 tablespoon Kilbeggan whiskey and 1.5 tablespoon sugar. Serve over chocolate ice cream. Cost, excluding the ice cream: around €2). If you think Irish milk and cream are expensive, don’t mention it to Irish farmers, who are only getting around 20 cent/litre for what should be a national treasure.

Is there better meat than meat produced in Ireland? Could anything from Brazil, Texas or Argentina compare to an Irish prime rib of beef on the bone, dry-aged for 17 days, from Nolan’s of Kilcullan or any of our other excellent butchers (roast 15 minutes to the pound and fifteen minutes over, serve on the pink side with crunchy seasonal garden vegetables & farmyard roosters. Cost of the beef: €12.90/kg). Are there better black or white puddings than those from some of our artisan producers, or are there better sausages? Perhaps the pork scare of last winter brought out a bit more appreciation for our rashers and hams and how we need to protect the quality and increase the pride in our produce. Our meats, done right, are stellar.

But quality doesn’t seem to be enough, at least not here at home. The Irish food industry is in transition, and many of those making, producing and serving our foods are in difficulty. I’m not an economist. I can’t say I have the answers to the big picture. I think about the people I know – food producers dropped from supermarket shelves, farmers who have taken huge loans based on grants that now seem will never be paid, small shopkeepers who wonder if it still makes sense to pass on the products they love to a public increasingly only interested in price, and talented chefs faced with emptying dining rooms. There’s enough worry out there to drive one to drink (a pint or two of the Porterhouse’s highly alcoholic Brainblásta might be just the thing if you feel the same way. Cost: €4.40/pint).

I wouldn’t expect any help from the government. They seem far too obsessed with pushing through NAMA (take all dodgy real estate investments, put in big pot, simmer for 10 years to try to improve palatability. Cost: €54 billion) to pay more than scant attention to both the plight and potential of farmers or food producers. Kate Carmody, an organic farmer in North Kerry, is turning away badly-needed orders from abroad for her Beal cheese because her local banks refuse to consider a loan for expansion (slice her aged, raw milk cheddar and serve with crackers and a glass of white wine. Cost of the cheese: €2 for 100gm). Would NAMA change this? There is nothing in the legislation to address her situation, and the government doesn’t even seem aware that there is an economy outside of their own budgets and the world of construction.

Consumers, pinched by rising taxes and the fear of falling wages and redundancies are cutting back, and food is one of the first targets for saving money, which means there will be food producers, restaurants, and shops that will close down. (If you are on a tight budget, it’s hard to beat an Irish egg, packed with protein and flavour, for a bit of sustenance. Boil, poach, fry, or scramble. Cost: 20-30 cent.) The fact that food prices have been lagging behind inflation (by a percentage point a year since 1982, according to figures supplied by Bord Bia), and that food is a smaller chunk of household income than it ever has been, will be of little comfort to someone struggling to make ends meet.

If there is a bright side to this, it is that Irish restaurants, producers and shops are looking more than ever at ways to improve value, both in terms of quality and cost. Farmers, squeezed by falling prices, are looking for new ways to sell their produce. According to Eddie O’Neil of Teagasc, they have received 30 inquiries in the last week from farmers looking to package their own milk, and farm shops are popping up everywhere. Farmer’s markets are also proliferating and can yield some of the best bargains and most satisfying shopping around. Denis Cotter, of Cafe Paradiso, suggests looking for pumpkins and squash, since they are perfect for the time of year (roast in the oven with a bit of olive oil, cumin, and ginger. Cost: You can probably haggle).

It’s hard for me to see the downward slide of Irish food continuing. In fact, I expect quite the opposite. Food is so interwoven with our society, it is one of the basics of life, and as I’ve said before, we’re really good at it. After years of excess, the basics will become more important than ever, and we will want to enjoy real quality of life. I think of my own baby girl – how everything stops when she is hungry, and how happy she is when feeding (attach baby to the breast. Cost: nothing, except keeping the mother well-fed). Ten years from now, NAMA comes due, and we can only guess where property prices or the economy will be at that point. We do know, however, that we will still be eating. We will need physical nourishment as well as the spiritual nourishment that comes with a great Irish meal enjoyed with loved ones. If food is a blessing, we are doubly blessed.

I promised a customer, who loved this tart, that I would post the recipe. It’s closely based on a recipe from Simply Sensational Desserts by Francois Payard, with the only difference a slight modification in the sugar. I have found that Payard’s book has given me the greatest baking success of any cookbook, so I highly recommend it.

I promised a customer, who loved this tart, that I would post the recipe. It’s closely based on a recipe from Simply Sensational Desserts by Francois Payard, with the only difference a slight modification in the sugar. I have found that Payard’s book has given me the greatest baking success of any cookbook, so I highly recommend it. 3 Lemons

3 Lemons

The

The  I am ashamed to admit that I’ve never been to the

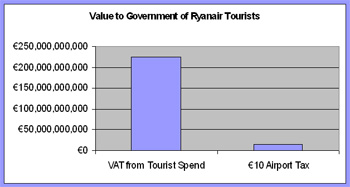

I am ashamed to admit that I’ve never been to the  As an ice cream man and not an economist, I’ve been trying to avoid getting angry about how the current economic mess is being handled in this country, but that is becoming increasingly difficult. The government seems to have only two plans of action: 1. Slash as much money as possible from their budget, and 2. Force through

As an ice cream man and not an economist, I’ve been trying to avoid getting angry about how the current economic mess is being handled in this country, but that is becoming increasingly difficult. The government seems to have only two plans of action: 1. Slash as much money as possible from their budget, and 2. Force through

This year, for Halloween, I made these awful looking eyeballs for our

This year, for Halloween, I made these awful looking eyeballs for our  Ingredients:

Ingredients:

I’ve been back a few days now, but it’s hard to get Venice out of my mind. Next time, I’m definitely going to stay more than a week! Anyway, for anyone who might be heading that way, and I do suggest it, you have a treat in store. There were so many highlights of the trip, but here are my top ten reasons to go back soon (in no particular order):

I’ve been back a few days now, but it’s hard to get Venice out of my mind. Next time, I’m definitely going to stay more than a week! Anyway, for anyone who might be heading that way, and I do suggest it, you have a treat in store. There were so many highlights of the trip, but here are my top ten reasons to go back soon (in no particular order): 1. Al Fontego dei Pescaori. Sottoportego dei Tagiapiera, Cannaregio. Two years ago, this was our favourite restaurant in Venice, and this visit we liked it even more. It’s traditional enough to satisfy Manuela, who is from Venice, and exciting enough to delight me. This time, they had a starter of pesce crudo, or raw fish, and they paired four fish with four fresh fruits. It was astonishingly good. They don’t serve food with a lot of fuss – they just choose the very best ingredients and serve things simply. Culinary heaven, great atmosphere, great wine list, great desserts, and they were extremely welcoming toward our little baby. In fact, the owner said, “There is nothing more important than children, and I’m always happy to cook up whatever a child would like.” Róisín will be weaned by the next trip…

1. Al Fontego dei Pescaori. Sottoportego dei Tagiapiera, Cannaregio. Two years ago, this was our favourite restaurant in Venice, and this visit we liked it even more. It’s traditional enough to satisfy Manuela, who is from Venice, and exciting enough to delight me. This time, they had a starter of pesce crudo, or raw fish, and they paired four fish with four fresh fruits. It was astonishingly good. They don’t serve food with a lot of fuss – they just choose the very best ingredients and serve things simply. Culinary heaven, great atmosphere, great wine list, great desserts, and they were extremely welcoming toward our little baby. In fact, the owner said, “There is nothing more important than children, and I’m always happy to cook up whatever a child would like.” Róisín will be weaned by the next trip… 4. Fish market. The fish market in Rialto is not as big as the one in

4. Fish market. The fish market in Rialto is not as big as the one in  6. Fresh fruit and vegetables. Coming from Ireland, the quality of the fruits and vegetables amaze. There’s a huge vegetable and fruit section at the fish market (above) but there’s also stands throughout town. You really can’t go wrong if you stick to the seasonal and local, and there’s lots of it… You will also find the prices extremely reasonable.

6. Fresh fruit and vegetables. Coming from Ireland, the quality of the fruits and vegetables amaze. There’s a huge vegetable and fruit section at the fish market (above) but there’s also stands throughout town. You really can’t go wrong if you stick to the seasonal and local, and there’s lots of it… You will also find the prices extremely reasonable. 8. Beautiful churches. The architecture in Venice is beautiful and some of the churches are just stunning. You can even catch reasonably-priced classical music concerts in some of them in the evenings (most often Vivaldi, who lived in Venice).

8. Beautiful churches. The architecture in Venice is beautiful and some of the churches are just stunning. You can even catch reasonably-priced classical music concerts in some of them in the evenings (most often Vivaldi, who lived in Venice). 10. Prosecco. Stopping into a bar for a pre-dinner snack and glass of prosecco (or a

10. Prosecco. Stopping into a bar for a pre-dinner snack and glass of prosecco (or a